0ur first question had to do with the origin of the "Sonor" brand name. According to Mr. Link, "The name was granted as a trademark by the Imperial Patent Office in Munich in 1907. The word 'sonor' comes from Latin, and means 'sound.' It was a very good brand name then; today the Patent Office wouldn't accept it because it is a descriptive term used in the general music industry. Expressions that must be used by others to describe their products cannot be protected with a patent today."

Sonor's prestigious reputation throughout the world is solidly established. (Remember the "Rolls-Royce Of Drums" ads?) As Horst Link guided the company over the years, was there a particular philosophy or goal that he tried to follow in order to achieve, maintain, and enhance that reputation?

"Over the many years I've worked here," he replies, "the primary goal was not-believe it or not-to maximize the profit. That was one of the goals, of course — otherwise a company cannot exist. But our number-one goal was to produce high-quality instruments. I didn't want to compete in price against the Japanese and Taiwanese. Our best chance for success was, and still is, to have better drums. With German craftsmanship and tradition, and experienced and motivated workers, we have always had that capability. Of course, this was only possible through a very close connection to top drummers and music educators. It was something that I was very pleased to do. Although we haven't become the biggest drum manufacturer, I firmly believe that we manufacture the best instruments in the world.

"Of course, we always watch very carefully what's going on in the market. It's a challenge for us not just to be able to keep our position, but also to extend it. What we are doing to compete with our Japanese competitors is to enter the Japanese market. They are buying only our leading-and most expensive-lines. It doesn't make sense to come into Japan with cheaper products. We are fighting our other competitors, not only on the top, but also on the lower levels, with the Force 2000, and we have added the Force 3000 for the middle. But the biggest market is on the bottom. We feel that it's possible for us to go after a bigger share of this interesting market, developing lines that can compete not only in quality but also in price. [Editor's note: In January of 1992, Sonor introduced its low-end Force 1000 series.]

"With the cooperation of Hohner around the world for distribution, we can approach the lowerlevel market. But not the lowest level. It remains important to us to have our instruments manufactured here, not in Taiwan or somewhere else. We had one very bad experience with an import kit a few years ago, called the International series. It was a flop. You do make mistakes from time to time, and we realized that we should never do it again.

"Today," Mr. Link continues, "our 'quality first' and 'drummers first' philosophy is considered very 'modern'-but I established it twenty or thirty years ago. We came out in the 1950s with our own newspaper, called the Sonor Drummer. At that time, it was quite sensational to do such things. Another important part of our philosophy is to be better at protecting the environment than others who don't care as much. We also strive to enhance the motivation of the 200-plus people who work with us. This doesn't happen everywhere."

Not many drum factories are situated in rural farm country. Why did the Links move the operation to the village of Aue, rather than to a city that might have been more convenient for shipping or other industrial considerations?

Horst Link explains, "At the time I started, I began making genuine skin drumheads, like my grandfather. They couldn't have been manufactured in an industrial area, because we needed clear, fresh water and good air. So the drumhead operation brought us here. It was an area where there were no people who knew about manufacturing musical instruments; at the time they were working in the woods or as farmers. It took long time to educate them, but once we managed it, we had very skilled and dedicated work force. We have people who've worked here for forty years! That's why they really know what they're doing. We don't have to worry about re-training some one every couple of weeks. Of course, it costs more money ship merchandise from here than from Hamburg. But you can't have everything; you have to have priorities. The employee and some other factors balance out the shipping inconvenience, and I see that as more important."

The announcement that Sonor had been sold to the Hohner corporation last year raised some questions within the drumming community regarding the status of the company. Ho Link explains the situation.

"On January 1, 1991, Sonor became part of Hohner. They a well-known corporation in Europe and around the world Sonor will operate independently, with its own distribution,

own customers, and its own endorsers. There will be many things in common with Hohner, of course, such as displays at trade shows. But percussion instruments are percussion instruments, and harmonicas are harmonicas, and you cannot put them all together.

|

|

Design And Development

The Sonor manufacturing complex fills several large buildings housing separate drum and percussion-instrument production departments. The entire operation would do justice to a Detroit auto plant. But that's not to say that industrial efficiency takes precedence over craftsmanship and the desire for quality. Quite the contrary: Sonor's elaborate and painstaking way of doing things is the result of a constant effort to achieve those very attributes. It's just that they make that effort on a pretty grand scale.

Sonor also does things on a minute scale. For example, the Sonor catalog features pages describing the results of extensive research into the acoustics and physics of drum design. In typical

Germanic style, nothing is left to chance; every element of drum design and construction is carefully considered before actual production begins. Over the years, that consideration has led to the development of a wide variety of drum lines, incorporating different woods and shell thicknesses. According to Karl-Heinz Menzel, Sonor's Product Manager, "An important part of our philosophy is to satisfy the various requirements of drummers for all types of music with reference to different sounds."

For many years, Sonor was noted for their extra-thick, extrastrong shells. In fact, a famous ad from the early 1980s shows a beefy workman crouched atop a tom-tom shell to illustrate its strength. The company's thickest shells, from their Signature Series, were introduced in 1980 and made of 12-ply, 11 mm thick beech. This thick shell was the result of research conducted by Sonor that indicated that a drumshell is "acoustically passive, and does not contribute notably to the sound projection of a drum." Further, -The shell must have great mass... [because] it favors an efficient projection of the fundamental tone." With the Signature series, Sonor became noted for heavy, low-sounding drums.

On the other hand, Sonor also realized that some drummers simply preferred brighter sounds than those produced by the Signature series. Their research indicated that "The basic frequency will be more muffled when the shell has a thin wall, so that the upper frequencies emerge. The sound seems to have more overtones, to be more brilliant and sustaining." 'Ib take advantage of these characteristics, in the mid-'80s the company introduced Sonorlite-a line that features 9-ply (7.5mm) tomtom and 12-ply (8.5mm) bass and snare shells of Scandinavian birch.

Responding again to market demand, Sonor introduced its first all-maple line of drums in 1988. These were the Hilite and Hilite Exclusive lines. Sonor added a special feature to this series-rubber insulators isolating all metal parts from the shell-in order to enhance vibration and supply "maximum sustain." The 9-ply (7.5mm) shells were designed to produce 11 a warm and full tone with precise attack." In 1991, the attributes of the Hilite line were applied to the Signature style of drum construction, resulting in the Signature Special Edition series, which features 12-ply maple shells with high-gloss lacquered African bubinga veneers, and Hilite-style acoustically isolated hardware (known as the Advanced Projection System).

Along with the development of top-quality lines, Sonor also addressed the entry-level and semi-pro market in 1990 and 1991 with the Force 2000 (9-ply poplar) and Force 3000 (9- and 11-ply birch) series. Both are designed to offer strong, lively sounds and powerful attack.

Who at Sonor is responsible for drum design and development? Karl-Heinz Menzel replies, "We work as a team. My job includes design, and I work with two engineers. We get ideas by sitting down and talking things over, and we also work with our endorsers to get ideas from them. That's an important contribution that they make to our program.

"Dealers also offer us ideas, and almost every week we get people coming to us with something that they have invented and want us to buy. We have to be very careful about that, though. In fact, I generally tell people, 'Don't come here with your idea until you have it patented.' When they ask why, I say, 'It may be that our engineers are working on something similar. If you come here and show it to us and we say no-and then we come out with our own idea shortly thereafter-you may think that we stole your idea and want to sue us. When you have a patent, we'll talk about it."'

|

|

Production

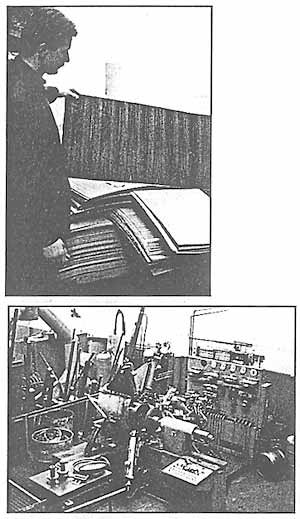

Once an item is designed, it's likely to be among the hundreds that are made in Sonor's huge machine shop-along with tools and equipment used to make still more items. Dozens of specially adapted machines are dedicated to a wide variety of turning, stamping, cutting, and shaping operations. Why operate such an extensive facility in-house?

"Because the best way to have quality under control is to produce everything yourself," replies Karl-Heinz. "The more components you buy from outside sources, the less control you have over the quality of those components. What we do buy from outside are rivets, screws, and minor assembly parts. But everything else we use to build our drums we make inhouse, including shells, hardware, rims, and drumheads. Sometimes our machines are too busy, and then other companies here in the area help us out. But in those cases, the tools they use for making the parts were made here in the company. This is important to understand, because it's a major reason that Sonor is more expensive than other products on the world market.

"We're not interested in taking part in a price war," KarlHeinz continues. "What we need are products with features and quality that give a dealer something to talk about in a drumshop. Someone could come into a shop and look at a drumkit and say, 'This is the same kit I could get from Taiwan, but it costs a thousand bucks more!' People need to understand why it costs a thousand bucks more. We have so many steps that we take care of in our production, it makes it more expensive. We have plenty of alternatives; we could make some of our drums more cheaply and drop the price 40%. But we don't want to do that, because in that case we would have the same quality level as our competitors."

Sonor's drums differ from those of their competitors in several specific ways. The manner in which their exotic-wood drumshells are finished is just one of those differences. KarlHeinz outlines the process.

"We use many special veneers to cover our drums, including African bubinga, rosewood, oak, and ebony. On our competitors' drums, the grain of the veneer goes around the shell. On ours, the grain runs vertically. The reason is that there are two different ways to produce a very thin veneer. One is to put a tree on a big turning machine and come around with a knife and cut the plies off. But we cut the tree in half lengthwise, and take plies out of the middle, in a vertical configuration. Our workmen have to take great care that the vertical grains of our veneer sections run symmetrically. No machine can do that; a skilled person must decide where to cut each veneer segment to fit it onto the drum to make the grain run symmetrically. This is a unique feature of Sonor drums; no one else places their veneers in this manner."

Sonor's attention to the details of drum physics is illustrated by the way they make the wooden tension hoops for their bass drums. Bass drum shells are under pressure from gravity, head tension, and the weight of any drums that might be mounted above them-all of which is vertical pressure against the circumference of the shell. Hoops, on the other hand, are under pressure from the tension claws pulling them against the drumhead Ñ a horizontal pressure. So Sonor actually makes the hoops in a different manner from the shells to account for this different direction of pressure.

"There are many steps in our production that we could save," says Karl-Heinz, "and at the end we would get a similar product. But we would not have all the features that make our products what they are. For example, there are two ways to make metal snare drums. One is to take a flat strip of steel and bend it around in a circle. This takes about ten seconds, and you have the basic shell. But you also have a welding seam there that will always cause an interruption in the vibration and the resonance of the shell. We start all our metal snare

drums-and tuning rims, as well-with a circular steel plate. We put the plate on a machine that presses and rolls it at the same time, turning it into a sort of pan shape. Then we cut the bottom out of the pan, and we have a drumshell or a rim.

"What makes our process better also makes it more expensive. One cost is time: It takes us about 12 to 15 minutes to press the material into the proper shape-versus ten seconds to bend a shell together. Also, the material itself is more expensive than normal steel, because it must have high elasticity in order to submit to this process. We do economize in one area, which is that we work down in size: The portion that is cut away from a large rim can be used to create a smaller one. And we use some of the material left over from the smaller rims to make clamps and other smaller items. We try to have very little waste. This is also true in our woodworking department. Ten years ago, all our wood scrap was thrown away. Today, it is the fuel source for the heating system for the entire company."

To appreciate the complexity of Sonor's tooling and assembly operations, one must examine the number of drum and hardware series offered by the company, then multiply that figure by the number of individual component parts for each item within each line. (Keep in mind that a bass drum pedal or a snare drum stand might involve a dozen or more separate parts.) Among those are small parts that once again reflect the company's focus on detail-such as special rivets. Stands are held together with full-metal rivets that are machined to form two separate heads. This is a timeconsuming process, but Sonor believes that it makes the connection virtually indestructible. As Karl-Heinz says, "The rivets on many stands work loose after a year or so, and eventually fall out. With ours, as long as you put a drop of oil on the moving parts from time to time, you might have one of our stands for 25 years or more. When you figure it that way, our 'more expensive' stands wind up being very economical in the long run."

All metal parts go from the manufacturing department into the sanding and polishing department before being plat

ed. After each part is plated, it comes back out to this department for a soft polishing and buffing. Karl-Heinz points out that Sonor's plating operation is another feature unique to the company.

"One of our big differences from all our competitors," says Karl-Heinz, "is that all our parts are triple-plated. You can put parts right into a chrome bath, and they'll look very good when they come out. But normal wear and tear will take the chrome off rather quickly. And chrome, by itself, is not a protection against rust, either.

"We start by putting the parts through a chemical and a high-frequency sonic cleaning before they go into the various chemical baths. Then we plate each part with nickel, then add copper, and finish with chrome. This is very important, because the nickel and copper together are the real protection against rust. With our copper-plated hardware (the Hilite Exclusive series) we go copper-nickelcopper. Then we put clear lacquer on the copper, because otherwise it gets green after a while."

Following plating, the final buffing process is an area where details are checked yet again. "Every single piece is taken in someone's hands for polishing," says Karl-Heinz, "so there is already some quality control happening. If they see that something is wrong with a part, they put it aside right away. It's a hard job; the operator has to sit all day long pressing small parts against a sanding or buffing wheel. But on the other hand, they make good money, and they carry a lot of responsibility."

Drum Construction

Sonor's woodworking operation is slightly smaller, but no less precise, than the metalworking department. It is here that very thin "plates" made of threeand five-ply birch, maple, etc. are turned into drumshells. Operators must carefully cut this material into the right sizes, because three of these plates will be used to create a shell. When they are pressed together in the mold, the outside plate must be the longest, while the inside must be shortest-with the middle plate sized in between. "They must be very exact," comments Karl-Heinz. "If the operators cut one millimeter too much, there will be a gap where the shell

should meet. If the plates don't close properly, you have an interruption in the sound and vibration of the shell."

The plates arc placed in a cylindrical pressure mold, with their scams staggered in order to gain the most strength. There is a separate mold for each size of shell. The mold heats up to 180' (centigrade) to "bake" the shell under both high pressure and high temperature. The time varies with the size of shell; a bass drum shell typically takes about 30 minutes. The plates are cut on an angle so that the inside edges can slide sideways a bit to ensure a perfect scam; the outside edges of the finished shell are trimmed to correct size.

One interesting feature of Sonor's shell-molding process is that inside pressure is only used on bass drums with an interior veneer finish. Otherwise, the natural inclination of the plies to open back up exerts enough force against the outside pressure of the mold to form a strong shell. And yet, once the shell is finished, that inclination has been eliminated. "When we take the shell out," says Karl-Heinz, "you could cut it right through the middle, and the plies would never try to open up. That means that there is no longer any tension within the shell. If you have that tension, the shell can't transport vibration. Our process prevents that from happening."

After the shells have been molded, they are trimmed to exact size, and then given their 45¡ bearing edges. They are then sanded inside and out, at which point they are ready to be covered or lacquered, depending on which line they are intended for. The company has three different lacquering departments: one for clear lacquering over natural wood finishes, another for high-gloss colored lacquer finishes, and one in which the copper-finished hardware pieces from the Hilite Exclusive series receive a protective coating.

The high-gloss lacquering operation is the most intricate, involving a six-step sanding/lacquering process and a special spraying room. Wien the final high-gloss lacquer coat is applied, the entire floor of the spraying room is flooded with water over half an inch deep, while air is pumped into the room under pressure. This ensures that absolutely no dust is 11 ---present during the spraying operation.

Additionally, the sprayers wear dust-free suits, and the room is sealed while spraying is taking place.

The only Sonor shells that are covered are those in the Force 1000 and Force 2000 lines. Karl-Heinz states that "Sonor is the only company that covers its shells the way we do. Many of our competitors place double-faced tape at both edges, then roll the covering on. But there is nothing gluing the covering to the shell in the middle. Of course, when the lugs are bolted on, the covering is held close to the shell. But you can still feel that there is space between the shell and the covering. A covering muffles a shell somewhat anyway, because it is of a completely different material. But if you make the drum with a space between the covering and the shell, the muffling is even more pronounced. We put a special glue on the whole surface of the shell and on the whole surface of the covering. Then a special machine that we built ourselves rolls the covering on under high pressure. When this is done, you would destroy the shell before you could get the covering off of it. This is important because this way we don't get as much muffling effect. The covering becomes more a part of the shell itself."

Covered or lacquered shells are drilled for lug, tom-mount, and other holes on a machine controlled completely by a computer. Shells are held on a rotating drum, while three different drills move into the various positions necessary to put all the required holes into the shell. Every hole is drilled within one rotation; the entire operation takes only a few seconds. This is important, because while Sonor is concerned with its high-quality image, it must also be concerned with maintaining price control in order to be competitive. To that end, production methods are streamlined wherever possiblesuch as using a machine to drill holes and a conveyer-belt assembly line to expedite the final assembly of some drums. The company prefers to economize on time, rather than on quality.

Even Sonor's method of assembling and preparing drums for shipping is unique, as Karl-Heinz explains. "We don't put heads on floor toms or bass drums," lie says, "because they're shipped in 'nested' packaging. We put the heads on rack toms, but we don't tune them, because every drummer has a different way of tuning tom-toms. But with snares, we feel that there is an optimum tuning range, and we take special pride in the fact that we actually tune every snare drum before we ship it.

"We place each drum on a stand in front of a microphone connected to a Strobotuner, and tap the drum with a small mallet. The operator goes around and around, tuning each lug until the pitch at that lug matches the desired pitch on the tuner-which will vary with the size and type of snare drum. Of course, a drum is never 100% tunable to a specific pitch. But we can come very close. This method may not give a tuning that every drummer would use, but it will at least create a goodsounding drum. We feel that this is important, since most stores don't tune a drum when they put it on their display floor. If a customer walks in and hits half a dozen snare drums, that customer is likely to buy the one that sounds the best right then and there. Since we instituted this operation, we've more than doubled our sales of snare drums."

Drumheads

Considering that Sonor got its start making drumheads, and that the West German operations began with the same product, it's not surprising to learn that Sonor is once again in the drumhead business-albeit after a significant absence. Karl-Heinz explains the company's re-entry into this highly competitive field.

"For years we used Remo heads exclusively on our drums-and sold them here in Germany. Most other drum companies also used Remo heads; they had something like a monopoly on the world market. Remo offered a good product, good price, good sound-no question. But then they started producing drums, too-and the other manufacturers said, 'Hey, what's going on? We spend millions of dollars on drumheads from Remo, and now they're using this money to become our competitor in drums.' So many companies have started using other heads--or making their own.

"We had our own plastic drumhead production for a while, but we stopped because, at the time, it was more economical to buy Remo heads than to make our own. But three years ago we decided to try making our own again. We also decided that it made no sense to come out with heads essentially similar to Remo's; they had to be different. The plastic films we are using are basically the same. There are some steps involving tension and temperature that are production secrets, but the most important difference is in how we hold the plastic material in the metal rims.

"We use an aluminum channel ring, with an outside edge that is higher than the inside edge. The plastic film is placed across this ring, and then a second, inner ring made of square aluminum bar stock is pressed into the channel ring. Then the machine turns around several times and rolls that higher outer edge over, folding it over the inner aluminum bar ring to lock it down and secure the head against pull-out. Other manufacturers use an inner-ring system, but no one else uses a square inner ring like we do. We've tightened our heads up to where the lugs pulled out of the drum, but we've never had a head pull out of the ring. As far as sales go, we are very strong in Germany and Europe; in the U.S. it's a price problem. But we are thinking about a promotional campaign and looking for some endorsers to use the heads exclusively. Basically, this department has only been running about two and a half years."

On December 6, 1991, shortly after MD's visit to Sonor, Horst Link announced his retirement as president of Jobs. Link GmbH & Co.KG/Sonor Drums. On January 1, 199Z, the Chairman of the Board of Hohner AG, Mr. Gunter Darazs, took the position of Managing Director, and Mr. Uwe Melzer from Hohner was appointed General Manager. In an open letter to the industry, Mr. Link, who will remain associated with the company as a consultant, stated: "We can proudly look upon the Sonor musical instrument business over the last 45 years. The merger with the international Hohner group presents a promising future.... The name Sonor will remain the standard by which percussion instruments of the highest quality will be measured." Considering both the history and the forward-thinking nature of the Sonor company, there's no reason to doubt Mr. Link's predictions.

|

|